Art Therapy Practices within Visual Art Education

Professional Learning Capstone - Semester 4, November 2021

INTRODUCTION

I acknowledge the Woiworung people of the Kulin nation, the Traditional Custodians of the land in which this research has taken place, as well as the Wurundjeri people of the land in which the University of Melbourne city campus stands. I pay my respects to their Elders past, present and emerging, and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across Australia today. I recognise that the land in which I have lived and grown up in is stolen and unceded, and I will continue to educate myself and my future students while prioritising Indigenous voices in the spirit of reconciliation. This is, and always will be, Aboriginal land.

I have always felt different. For as long as I can remember, even in kindergarten and primary school, I was aware that I acted a certain way, and had trouble making relationships with my peers. When I got to high school, this feeling was amplified by adolescent expectations to fit in, be popular, follow trends, and be like everybody else. I spent my high school years feeling like something was wrong with me because I struggled with things that everyone else seemed to find easy. I developed bad depression, anxiety, and unhealthy coping mechanisms, and spent years with a myriad of different school counselors, psychologists and psychiatrists, trying to figure out how I could feel ‘normal’. It wasn’t until I was 20 years old that I was diagnosed with Autism, and my whole perspective on who I was changed. I began to understand things I had been confused about for so long, and was able to begin the process of learning to be my authentic self.

Looking back at my time in secondary school, it is synonymous with my poor mental health. These experiences, though hard, shaped me into who I am today, and evidently led to me wanting to become a visual art teacher in order to support those going through similar struggles. Poor mental health issues are rising and causing concern worldwide. In the past decade, there has been a 13% increase in reported mental health cases, and the average time of the disability lasting is between one and five years (WHO, 2021). Many of these concerns commonly occur during adolescence (Hankin, 2006). The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2020) records that 14% of children and adolescents aged between 4 and 17 experience a mental health disorder. In 2014, the Young Minds Matter survey found that roughly 11% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 had deliberately hurt or injured themselves, and in 2018, over 3,000 people died from these injuries (WHO, 2021). Beyond Blue (2021) reports that over 75% of mental health disorders occur before the age of 25, and 50% before the age of 14 (Kessler, 2005), with suicide being the leading cause of death for young people in Australia. Unfortunately, young people are the least likely of any age group to seek professional help (Slade, 2009), with only 31% of females, and 13% of males with mental health problems seeking professional help.

Young people are evidently reluctant to seek help on their own. My own experiences involved my school following their duty of care and reaching out to my parents, and help was found for me. For a long time, however, I was reluctant to participate and believed I was beyond the point of no return. I felt alone in my experiences, and did not believe anyone would understand what I was going through. Unfortunately, this is the perception of many young people today. Many reasons have been proposed to explain why young people do not seek help, including issues associated with cost, transportation, inconvenience, confidentiality, feelings of wanting to handle problems independently, or, like I once felt, the belief that treatment will not work (Mojtabai, 2001). Two reviews of help-seeking studies (Rickwood et al, 2005; Rickwood et al, 2007) concluded that a high reliance on oneself to solve problems, lack of emotional competence and negative attitudes towards seeking help were large barriers for young people, resulting in friends and family more often being the prefered sources of help over professionals (Gray & Daraganova, n.d.).

For students, their mental health and wellbeing has a consequential impact on their learning and academic success (Gaudry & Spielberger, 1971), in addition to their social, physical and emotional performance. These concerns affect energy levels, concentration and optimism, leading to extreme discomfort and hindering their ability to learn. While the Australian government has implemented initiatives such as Headspace, Beyond Blue and Kids Help Line to educate students about these issues, and provide knowledge about getting support, Victorian teachers continue to feel overwhelmed by mental health problems within schools. In June of 2019, the Victorian branch of the Australian Education Union conducted a survey with over 3,500 government school teachers about mental health, with less than half of teachers reporting that they felt their school had access to adequate mental health services. This survey also confirmed that poor mental health has a severe impact on the classroom environment (80%), significantly so for VCE (85.1%). There is an urgency to address and make changes to the current education system to help students at a preventative level, as well as improve strategies for those already affected.

This research proposes the question: how can art therapy practices be used in art education to support student wellbeing? There is limited literature relating to art therapy practices placed within an educational context, particularly in Australia. Many of the relevant literature discusses the overlapping features of art therapy and art education, but is limited in the integration of both together. Efland (1975) discusses the proposing factors between the two, asserting that criteria should have no place within a clinical setting, while discouraging teachers from thinking of themselves as therapists. Consequently, while Dunn-Snow and D’Amelio (2000) discuss how art teachers can make the artmaking process more therapeutic, they ultimately conclude by discussing interdisciplinary teams, which would allow the art therapist and art educator to remain separate roles. This study aims to explore how those roles can be combined in order to facilitate therapeutic outlets for students within secondary schools to explore and express their concerns.

METHODOLOGY

At the peak of my mental health troubles, I often turned to art to express how I felt, and what I often had trouble verbalising. Creating art became a way for me to release negative emotions, and was often more productive and helpful than the health care professionals I was so reluctant to talk to at the time. This practice continued well into my undergraduate Visual Arts degree, and became my main artistic practice when I began to understand my Autism diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Pidgeon, R. (2014). Self Portrait [drawing].

Art as therapy and student wellbeing are two things that I have become very passionate about in my journey to becoming an art educator. As such, this self-study research project aims to develop an approach to art education that allows art in / as therapy approaches to be used to provide students with an outlet to express and explore their concerns, as well as implementing a culture of wellbeing into the classroom.

The self-study model, as described by Samaras (2011), is a personal inquiry that uses reflections and experiences as the bases of research in order to improve one's role and actions. While being positioned as a teacher-researcher, the aim of this model is to generate and present my own knowledge while improving my own and future students’ learning. This study will use multiple methods of data collection, including examining my personal history through critical autoethnography, a/r/tography, reflective practices, and reviewing literature. By engaging and reflecting in the explored practices, I will reflect upon my own experiences in order to understand cultural experiences. Creating and reflecting upon my own artworks as da(r)ta will allow me to analyse my thinking processes to determine the effectiveness of these practices. Finally, I will use my findings to propose ways in which these practices can be adapted to be used within an art education setting.

WHY ART?

Art has always been a method of communication and expression since prehistoric times, when our ancestors first marked cave walls over 40,000 years ago. As humans, we naturally learnt to use art as language when we were children, beginning with scribbles and lines as a way to express our needs, often before verbal language was developed (Shemps, 2008). Whether we are creating or viewing it, art allows us to explore emotions, develop self awareness, cope with stress and improve social skills (Cherry, 2020).

It has become widely believed that art, in some way or another, reflects the psychic experience of the artist. Well known artists have been plagued with their own mental health conditions, and even in recent times we have seen performers in creative arts industries struggling with mental health, such as Robin Williams and Bo Burnham.

A notable example, Vincent Van Gogh, is infamous for cutting off his own ear and later taking his own life. He wrote to his sister in 1889, “I am unable to describe exactly what is the matter with me. Now and then there are horrible fits of anxiety, apparently without cause, or otherwise a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the head”. Arguably his most well known artwork, The Starry Night (1889) was created when Van Gogh was incapacitated for his mental health, and is said to depict the view from the asylum he was in. Similarly, The Scream (1893) has captured Edvard Munch’s anxiety and internal torment, which fuelled his art. His inspiration for the painting came from an evening night, where he watched the sky turn red and was filled with tremplying anxiety as he felt the “infinite scream” through nature. Munch wrote in his diary, “my fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness… My sufferings are part of myself and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art” (McDonald, 2013). These two artists sewed together their mental health with their artistic practice, creating a continuity between their outer physical environment and their inner psychological environment.

Figure 2.

Van Gogh, V. (1889). The Starry Night [painting].

Figure 2.

Van Gogh, V. (1889). The Starry Night [painting].

These examples make one wonder if art is a cause of these mental health concerns, or if mental health simply aids creativity. Recent advances in biological, cognitive and neurological sciences have led to new evidence that supports the link between art and mental health. Studies have shown that creating art reduces cortisol levels in the brain, leading to reduced stress and a positive mental state (Kaimal et al, 2016; Beerse et al, 2019).

A 2011 study, conducted by Professor Semir Zeki, sought to determine “what happens in the brain when you look at beautiful paintings” (Mendrick, 2011). Participants were shown a series of 30 paintings by artists including Guido Reni, Claude Monet, Paul Cezanne and Heironymus Bosch. Brain scans revealed that when they viewed the artworks that they deemed the most beautiful, there was a blood flow increase of up to 10% to part of the brain, which is equivalent to gazing upon a loved one. Zeki discerned that, regardless of the type of artwork, there was strong activity in the part of the brain that relates to pleasure. A later study (Nielsen et al, 2017) reiterated this conclusion, finding that when art was displayed within a hospital setting, patients experienced feelings of enhanced safety and satisfaction, as well as contributing to their positive health outcomes.

Evidently, art actively engages the brain. The brain is made of two hemispheres interconnected by a massive band of nerve fibres. The left side of the brain controls the right side of the body, and vice versa. Certain parts of the brain work together simultaneously, and each is responsible for specific functions. When we participate in art and creativity, our brains communicate between many centres of activity across both hemispheres. These different types of communications are called brain networks, and creativity engages three of them (Big Think, 2020). The Executive Attention Network holds information in your working memory, maintains strategies and accesses remote associations rather than obvious responses. This is what allows us to brainstorm ideas further than simply the first thing that comes to mind. The Default Mode Network or the Imagination Network is used when we focus our attention inwards, such as when we daydream, think about our future goals or imagine the perspective of someone else. Finally, the Salience Brain Network is what determines whether or not we find something interesting, and then feeds that information to the other two networks. Therefore, art and creativity is a whole brain activity. Creativity occurs when we are captivated by the moment, imaginative and motivated. In the words of Eric Jensen (2001), “the systems they nourish, which include our integrated sensory, attentional, cognitive, emotional, and motor capacities, are, in fact, the driving forces behind all other learning.” The process of art making helps develop these neural systems, and produces a range of benefits, including improved fine motor skills and emotional balance (Phillips, 2015). When we make art, we are creating a sequence of choices to solve problems, therefore supporting cognitive development. The brain is a predictive machine, always consciously and unconsciously trying to imagine what is going to happen as well as prepare ourselves for it. Art provides a means for us to navigate the problems that might arise. Therefore, the act of imagining is an act of survival (Gharib, 2020).

ART IN THERAPY

Officially recognised art therapy, or art in therapy, dates back to the 1940s, coined by educator and therapist, Margaret Naumberg. The concept was developed during the Freudian era of Id psychology. Using the metaphor of an iceberg, Freud suggests that the mind is made of three levels. Consciousness, the tip of the iceberg, is our immediate thoughts and perceptions. Preconsciousness holds our stored memories and knowledge that can be made conscious through prompts. The unconscious, like the iceberg, is the most important part of the mind that you cannot see. Unconsciousness is responsible for our behaviour, feelings and motivations (Codrington, 2018). Art in therapy aims to access and understand these three levels.

Art in therapy is undertaken with a licensed therapist who takes on the role as a facilitator rather than an authority figure. No previous artistic skill is required, as the focus of art in therapy is not on the final product, but on the act of creating. Art therapists meet people where they are in order to create “an oasis of creative experimentation” (Councill, 2015) within a treatment environment. The therapist does not interpret the work made, but works with the client to discover what they were thinking during the art making process, with the essence of the therapeutic practice lying within the act of creating something and making personal marks.

My original intention was to meet with a friend who is a licensed art therapist and use the art I created with her as da(r)ta, however at the present time I have been unable to do that because of the ongoing pandemic and lockdown at the time of research. I recognise that the main difference between art in therapy and art as therapy is the company of a licensed professional, so the da(r)ta I have created is not from an authentic art in therapy experience. Instead, I have drawn upon activities discussed in Susan I Buchalter’s Art Therapy Techniques and Applications (2009). This book, directed towards art therapists, outlines activities to do with clients and provides prompts for discussion.

The chosen activity, called ‘My History’ (page 112) asks clients to use images from magazines, or personal photos if desired, to create a collage that reflects various aspects of life from youth to adulthood. The goal of this activity is to recognise the role of past experiences on one’s present mood and behaviour, through reminiscing and self-awareness. To substitute the discussion with the licenced art therapist, I reflected on the activity and the prompt through journaling.

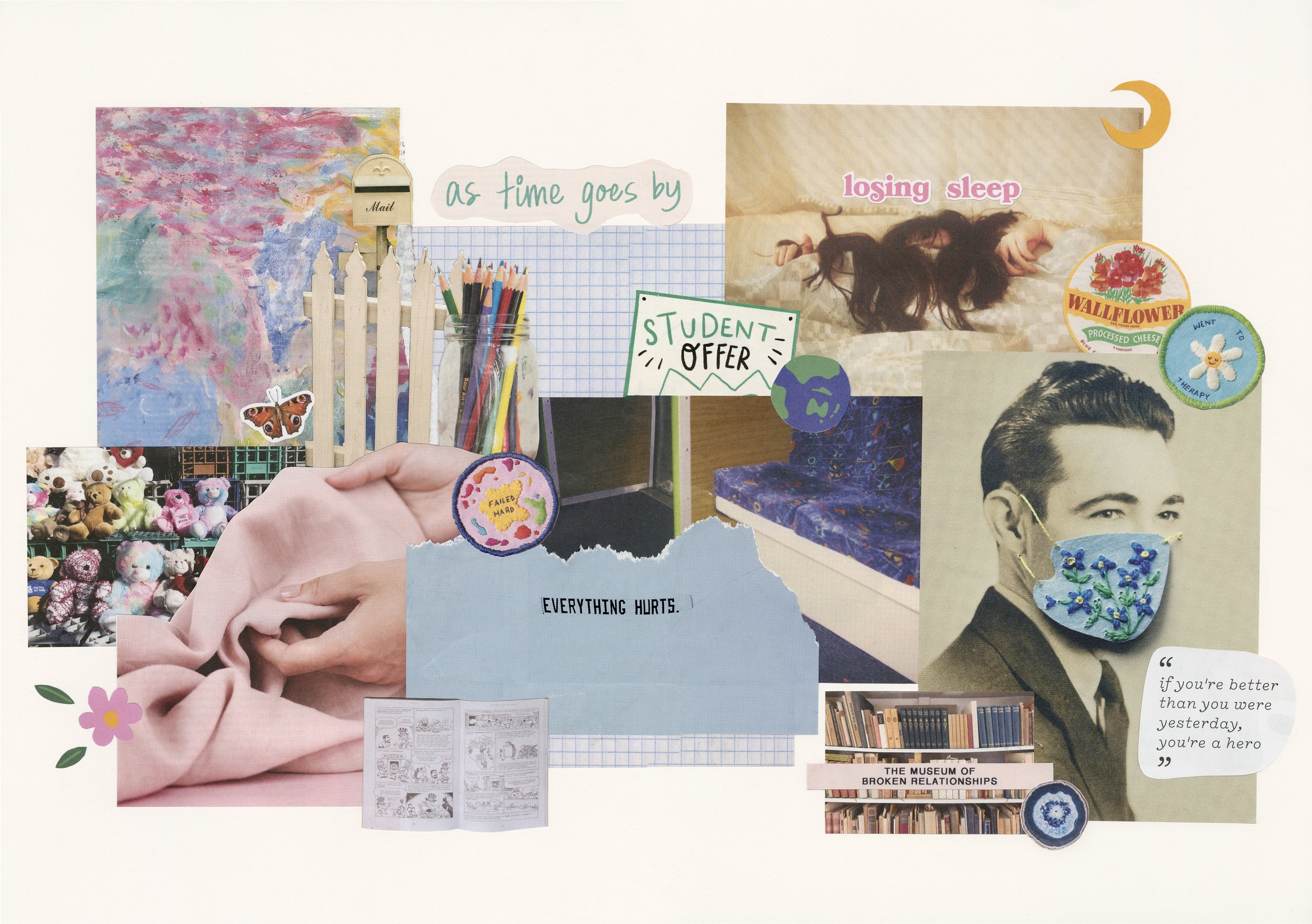

Figure 4.

Pidgeon, R. (2021). My History [collage].

The artwork I made is considered both a visual product of my knowledge as well as the process of embodied knowledge production. I had nothing in mind when looking through magazines, and instead allowed whatever came up to prompt memories from my pre-consciousness. In my journal reflection, I wrote: “I think I expected more negative memories to arise, and of course they did, but so did happier memories like my collection of items with butterflies from when I was younger, the rock and crystal collection I have now, travelling with my family in high school, and all the art I used to make as a child. I was even able to reflect on things like how my relationship with food has changed since becoming intolerant to dairy, and my personal growth mentally.

“[I have] unintentionally categorised my life into three phases, a colourful, carefree childhood, a challenging adolescence, and where I am now, trying to cope with world events and the future while still working hard to improve myself.”

This activity allowed me to view my life as an assemblage - webs of pieces placed together from past and present experiences (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). The relationships between my experiences, and each decision I have made, has led to where I am now. As I share and create new experiences, my assemblage becomes fluid and disrupted, and new possible ways of being are produced. The transformative nature of visual art, through the conversion of materials and emotions, and the activation of art’s sensory and imaginative qualities, allowed me to challenge the way I think. The skills of critical and analytical thinking means visual arts holds this potential to allow one to make sense of their own experiences and perspectives (Piazza, 2017).

ART AS THERAPY

Art as therapy, similarly, connects with the arts as a method of healing, but without the company of a licensed therapist. Through my self-study data, I have determined two different categories of art as therapy which I will refer to as mindful art as therapy, and expressive art as therapy.

Mindful art as therapy focuses on the calming nature of the art making process. For example, colouring, origami and drawing patterns are all process-focused activities that promote relaxation and mindfulness. A 2020 study (Hsu et al.) found that Zentangle art - a non-representational, unplanned and structured pattern drawing, often only consisting of simple, basic and repetitive lines and shapes - reduced psychological distress and enhanced participants' self-efficacy. This study also found that drawing therapy allowed participants to relieve and reduce stress and frustration, and lead to improvement in work performance, and in turn their physical, mental and spiritual care.

Throughout this year, I have kept a sketchbook dedicated entirely to mindful art. This sketchbook became a place for me to draw or paint in with no pressure on what the final artwork would look like. I drew whatever I wanted with no pressure to show anyone, experiment with styles and materials, and overall prioritise the calming and mindful nature of the art making process. Not only did this provide a way for me to soothe during stressful emotions, but I consequently ended up developing my art skills and becoming more confident in my individual style.

Figure 5.

Pidgeon, R. (2021). Paul Rudd [sketchbook drawing].

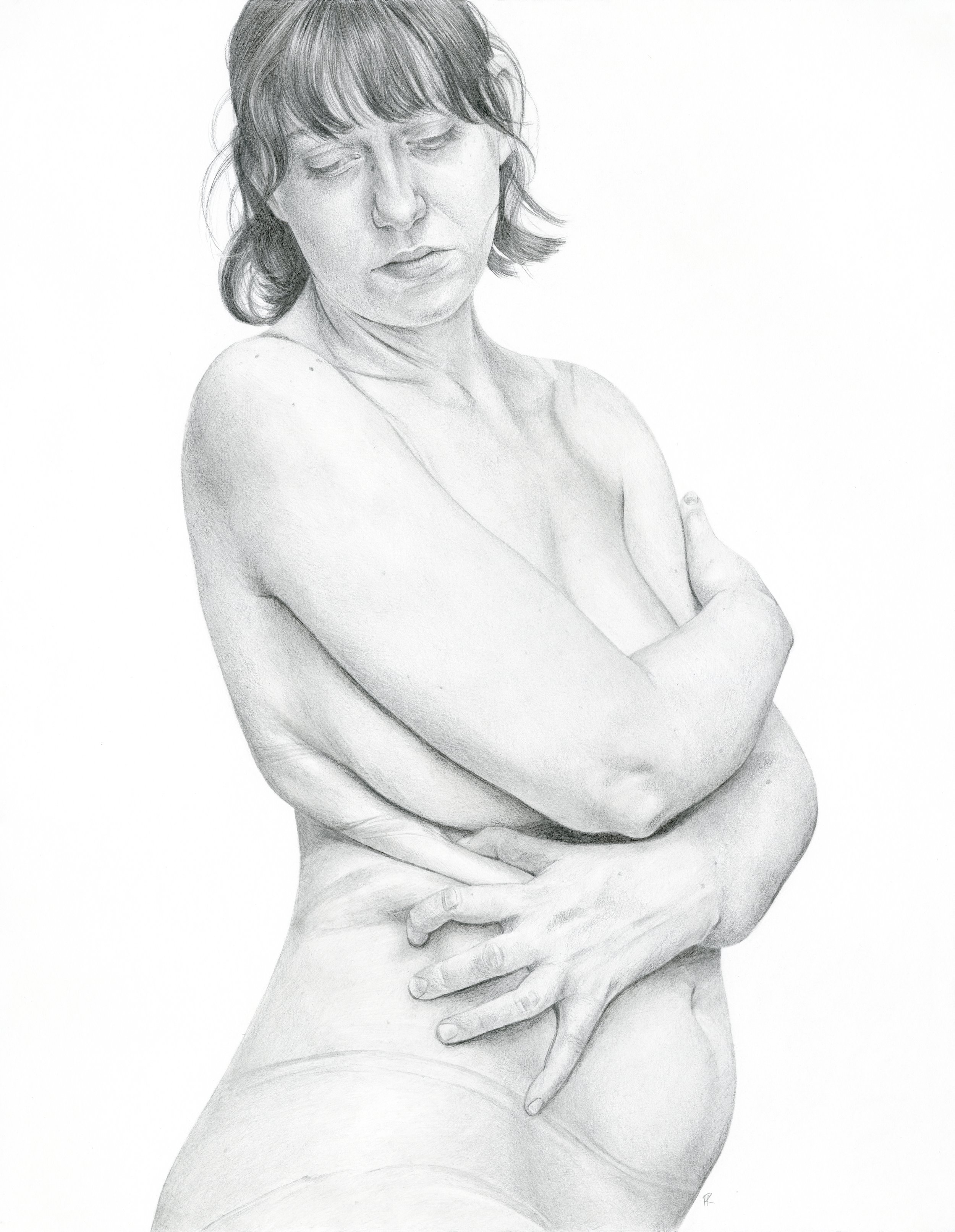

Expressive art as therapy explores emotions explicitly in a way that releases or understands negative feelings. Expressive art as therapy has become a key factor in my artistic practice, and is often used particularly within self portraiture as a way to externalise my feelings by turning them into a physical, neutral form, which I am then able to distance myself from. After my autism diagnosis, I created a series of three works that explored the idea of how my life would have been different if I had been diagnosed earlier, and I was subsequently able to reflect and understand the emotions I was experiencing through these artworks. This practice has mostly been quite successful in achieving these desired outcomes. However, as part of this research, I used this strategy as a way to explore body image and how I felt after gaining weight during lockdown. While I was happy with how the final drawing turned out, the process of creating it while having to refer to images that prompted negative thoughts was quite confronting. From this experience, I can determine that this strategy of expressive art as therapy can only work effectively with certain situations, only when one is ready and willing to confront the ideas being explored.

Figure 6.

Pidgeon, R. (2021). Renaissance Beauty [drawing].

PROPOSAL

The benefits of the ideas discussed have mostly been helpful for me personally. Students want and need a place to discuss their emotions (Berman, 2001), and using these ideas can provide that opportunity for them. The question still remains, however, of how these practices can be adapted to work in the art classroom. While some art therapy programs currently exist within Australian schools (Niemi, 2018), they work outside of the classroom setting in an art in therapy setting, typically with individuals with special needs. These programs, however, have the potential to help all students. Ideally, schools would have the funding to allow more educational creative arts therapists to work alongside wellbeing directors, school counsellors and art teachers. This would allow both art in and as therapy approaches to be used. Therefore, through reflecting on these experiences and my own da(r)ta, I have created three guidelines on how art as therapy, with ideas from art in therapy, can be used within traditional art education to support and promote positive student wellbeing for all students.

1. Eliminate the expectation that what students make has to look ‘good’, and emphasise the process rather than the finished product.

Through creating my self study da(r)ta, I found the most useful aspect of creating art to promote calmness and mindfulness was eliminating the expectations I placed on myself about how the final artwork should look. This did, of course, take some practice. I have a habit of abandoning sketchbooks when I am not entirely happy with how particular drawings turn out. The very first drawing in the sketchbook used for this research caused a completely irrational negative response from me because I didn’t like the composition of where it was placed on the page. I ended up writing a lengthy journal entry reflecting on why this had become a huge trigger for me, and from then on I consciously decided that it was okay if I didn’t love how the art I made turned out. I enjoyed the process of creating it, and that was all that mattered.

This may be tricky for students to learn, especially for VCE students where their sketchbooks and folios are all marked as part of the assessment. Therefore it is important to establish this within early years of art education. Additionally, encouraging students to keep a sketchbook that will not be seen by the teacher can eliminate pressures placed on students due to curriculum and assessment, and allow them to focus on and enjoy the process of making art.

However, this guideline relies heavily on the classroom space being a judgement free environment, referring to both the teachers’ judgement and peer judgement. The arts are often seen as ‘soft’ subjects (Scholes & Nagel, 2012), perpetrated by the idea that they are heavily female dominated. A focus on the art making process can provide a space where all students, particularly males, feel safe enough to experiment and make mistakes.

2. Implement personal history into topics to allow students to explore their own experiences and emotions.

For me, art has often provided a way to express things that I couldn’t do so verbally. As discussed previously, children develop art as language often before verbal language. Therefore it is only natural to encourage art as language as students get older. Incorporating opportunities for students to tackle personal ideas through expression can allow students to explore, deconstruct and examine their identity and experiences in a counter-hegemonic way. Nurturing their wellbeing in a supportive, non-judgemental and compassionate environment assures students that their way of expression and creativity are correct and valued.

It is important, however, to make this a choice for students. No one should feel forced to confront topics through art if they are not ready to do so. While later years in secondary school allow students to choose their subjects, art remains compulsory for younger year levels. This is especially important to consider for these younger students, as unwilling and non-participative students risk disrupting the process and wellbeing of other students. Individual success depends on the student’s willingness to partake in these practices, so forcing students who do not want to will not see the expected benefits. It is more important for students to feel safe and supported in the classroom.

3. Introduce a reflective journal practice at the end of lessons or units.

I found an integral part of the processes I explored to be reflecting on what I had made and the thoughts that accompanied it. Unless schools have the funding to employ educational creative arts therapists, then other methods that allow for reflection and discussion should be utilised. I propose that teachers should explicitly teach their students the skills for reflective journaling in order to explore processes and thoughts. Setting time aside in lessons for students to write and reflect on the art making process and any ideas or emotions they experienced allows students to develop self-awareness and see the benefits and purpose of art education within their own lives. Additionally, this practice promotes the development of critical and creative thinking through metacognitive skills. Critical thinking within students’ lives has the potential to support their social and emotional development, and additionally contribute to their lifelong learning. Our thought processes are influenced by our biases and distortions, so by analysing and evaluating how we think and what we think we know, we systematically improve the quality of our thoughts, and consequently the quality of our lives.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The statistics of young people who are at risk of developing, or have already developed mental health concerns is alarming, and schools have a responsibility to provide support for these issues. I have experienced the benefits of using art to improve my own wellbeing, and as an autistic woman with lived experiences of my own mental health issues during high school, I am in a position to understand and support the challenges young people may face. This self-study research has explored research on how art physically affects the brain in order to promote healthier mind sets, while engaging in both art in and as therapy practices through the use of autoethnography and a/r/tography. The experiences outlined within this research has emphasised the importance of why I began this process of becoming an art teacher, and has helped me understand further how I can use art as a way of supporting student wellbeing during this critical period in their lives. While these proposed guidelines are only the beginning steps for making art education more therapeutic, future research will be needed to determine the effectiveness of these strategies for my students. This involves learning alongside my students, and adapting my practice to meet their individual needs. Furthermore, this research has outlined additional opportunities for me as a teacher-researcher, and has led me to see the benefits in undergoing a creative arts therapy degree as professional development for being an art educator. An art educator’s primary job is to share knowledge, build a warm environment and mentor students, while an art therapist provides resources and insight into an individual's wellbeing. Having both of these skills would allow me to be fully dedicated to helping and nurturing individuals through art.

Australian Education Union Victorian Branch. (2019). Mental Health Royal Commission.

Australian Education Union. https://www.aeuvic.asn.au/sites/default/files/PDFs/AEU%201908%20MEM%20MHRC%20backgrounder.pdf

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Health of Young People. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-young-people

Beerse, M. E., Van Lith, T., Pickett, S. M. & Stanwood, G. D. (2019). Biobehavioural utility of mindfulness-based art therapy: Neurobiological underpinnings and mental health impacts. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 245(2), 122-130. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1535370219883634

Berman, J. (2001). Risky writing: Self-disclosure and self-transformation in the classroom. University of Massachusetts Press.

Beyond Blue. (2021). Young People. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/who-does-it-affect/young-people

Big Think. (2020, July 3). Creativity: The Science Behind the Madness [YouTube Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNHDTvqbUm4&ab_channel=BigThink

Buchalter, S. I. (2009). Art Therapy Techniques and Applications. Jessica Kingsley Publishing. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/teachers-warn-they-re-overwhelmed-by-mental-health-problems-in-schools-20190821-p52jgj.html

Cherry, K. (2020). How Art Therapy Is Used to Help People Heal. Very Well Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-art-therapy-2795755#:~:text=1%EF%BB%BF%20Art%2C%20either%20creating,tool%20in%20mental%20health%20treatment.

Claire Codrington. (2018). Conscious, Preconscious and Unconscious - Freud [YouTube Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spv-q975oVE&ab_channel=ClaireCodrington

Councill, T. (2015). Art therapy with children. In D. E. Gussak & M. L. Rosal (Eds), The Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy (242-251). Wiley-Blackwell.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia [2nd ed.]. University of Minnesota Press.

Dunn-Snow, P. & Georgette D'Amelio. (2000). How Art Teachers Can Enhance Artmaking as a Therapeutic Experience. Art Education, 53(3), 46-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2000.11652391

Edvard Munch. (2021). The Scream. https://www.edvardmunch.org/the-scream.jsp

Efland, A. (1975). Books on Art Therapy: A Personal Comment. Studies in Art Education, 16(2), 67-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.1975.11651341

Gaudry, E. & Spielberger, C. D. (1971). Anxiety and Educational Achievement. Wiley.

Gharib, M. (2020). Feeling Artsy? Here’s How Making Art Helps Your Brain. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/01/11/795010044/feeling-artsy-heres-how-making-art-helps-your-brain

Gray, S., & Daraganova, G. (n.d.). Adolescent help-seeking. Growing Up in Australia; Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/research-findings/annual-statistical-report-2017/adolescent-help-seeking

Hankin, B. L. (2006). Adolescent depression: Description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy & Behaviour, 8(1), 102-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.10.012

Hsu, M. F., Wang, C., Tzou, S. J., Pan, T. C. & Tang, P. L. (2020). Effects of Zentangle Art Workplace Health Promotion Activities on Rural Healthcare Workers. Public Health, 196, (217-222). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.05.033

Jensen, E. (2001). Arts with the Brain in Mind. ASCD. Kaimal, G., Ray, K. & Muniz, J. (2016) Reduction of Cortisol Levels and Participants’

Responses Following Art Making. Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 33(2), 74-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1166832

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., Walters, E. E. (2005).

Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593-602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

McDonald, J. (2013). Prince of Darkness. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/prince-of-darkness-20130620-2ojt8.html

Mendrick, R. (2011). Brain scans reveal the power of art. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-news/8500012/Brain-scans-reveal-the-power-of-art.html

Mojtabai R. (2001). Unmet Need for Treatment of Major Depression in the United States. Psychiatric Services 60(3), 297-305. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.297

Museum of Modern Art. (2021). The Starry Night. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79802

Nielsen, S. L., Fich, L. B., Roessler, K. K., & Mullins, M. F. (2017). How do Patients Actually Experience and Use Art in Hospitals? The Significance of Interaction: a User-Oriented Experimental Case Study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2016.1267343

Niemi, S. (2018). Integration of Art Therapy and Art Education [Master’s Thesis]. The University of Wisconsin Superior. https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/78788/Niemi-Integration%20of%20Art%20Therapy%20and%20Art%20Education.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Phillips, R. (2015). Art Enhances Brain Function and Well-Being. The Healing Power of Art & Artists. https://www.healing-power-of-art.org/art-and-the-brain/

Piazza, L. M. (2017). Exploring the Artistic Identity / Identities of Art Majors Engaged in Artistic Undergraduate Research [Doctoral dissertation]. University of South Florida. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8125&context=etd

Rickwood, D., Deane, F., Wilson, C. & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Young People's Help-Seeking for Mental Health Problems. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 4 (3). https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.3.218

Rickwood, D., Deane, F. & Wilson, C. (2007). When and How do Young People Seek Professional Help for Mental Health Problems? Med J Aust. 2007, 187(7), 35-39. https://doi.10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01334.x

Samaras, A. P. (2011). Self-Study Teacher Research: Improving Your Practice Through Collaborative Inquiry. Anastasia.

Scholes, L. & Nagel, M. C. (2012). Engaging the creative arts to meet the needs of twenty first-century boys. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(10), 969-984.https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.538863

Shemps, J. L. (2008). The Need for Art Therapy in Middle Schools. [Master’s Theses, The College at Brockport]. https://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1097&context=edc_theses

Slade, T., Johnston, A. K., Teesson, M., Whiteford, H., Burgess, P. M., Pirkis, J. & Saw, S. (2009). The Mental Health of Australians 2: Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing.

Van Gogh’s Letters. (1989). Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Wilhemina van Gogh. http://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/19/W11.htm#:~:text=I%20am%20unable%20to%20describe,thing%20as%20a%20simple%20accident

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2021). Mental Health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health

Young Minds Matter. (2014). The Mental Health of Australian Children and Adolescents Overview. https://youngmindsmatter.telethonkids.org.au/siteassets/media-docs---young-minds-matter/ymmoverview.pdf